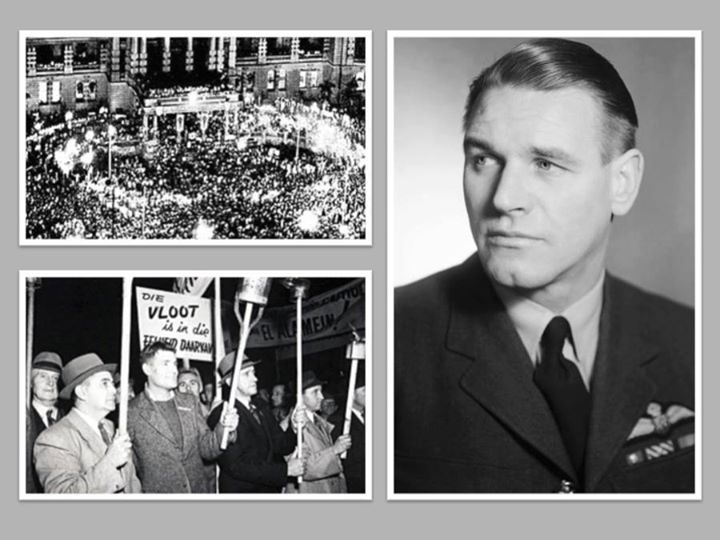

Another inconvenient truth to the current political narrative of the “struggle”, the first mass anti-Apartheid protests where led by this highly decorated Afrikaner war hero – Adolph “Sailor” Malan – and the mass protesters were not the ANC and its supporters, this very first mass mobilisation was made up of “White” war veterans – read on for some fascinating “hidden” South African history.

Many people may know of the South African “Battle of Britain” Ace – Adolph “Sailor” Malan DSO & Bar, DFC & Bar – he is one of the most highly regarded fighter pilots of the war, one of the best fighter pilots South Africa has ever produced and he stands as one of the “few” which turned back Nazi Germany from complete European dominance in the Battle of Britain – his rules of aerial combat helped keep Britain in the war, and as a result he, and a handful of others, changed the course of history. But not many people are aware of Sailor Malan as a political fighter, anti-apartheid campaigner and champion for racial equality.

“Sailor” Malan can be counted as one of the very first anti-apartheid “struggle” heroes. The organisation he formed “The Torch Commando” was the first real anti-apartheid mass protest movement – and it was made up primarily of “white” South African ex-servicemen. Yet today that is conveniently forgotten in South Africa as it does not fit the current political rhetoric or agenda.

Born in Wellington, Cape Province, in 1910 Malan joined the Union Castle Line of the Mercantile Marine at the age of 15, from which service he derived his nickname “Sailor”.

He foresaw the onset of war with Nazi Germany, promptly went off to Britain and learned to fly at a flying school near Bristol, England where he received his pilot’s wings. In 1936, he was posted to No. 74 (Fighter) Squadron (known as the “Tiger Squadron”). It was his first and only squadron, and he is regarded as the squadron’s most famous fighter pilot of all time. In total Malan destroyed 27 Nazi German Luftwaffe planes and damaged or shared another 26 all the while flying the iconic Spitfire.

After the Second World War, Sailor Malan left the Royal Air Force and returned to South Africa in 1946. He was surprised by the unexpected win of the National Party over the United Party in the General Election of 1948 on their proposal of “Apartheid” as this was in direct opposition to the freedom values he and all the South African veterans in World War 2 had been fighting for.

What he and other returning World War 2 servicemen saw instead was far right pro Nazi Germany South African reactionaries elected into office. By the early 1950’s the South African National Party government was littered with men, who, prior to the war where strongly sympathetic to the Nazi cause and had actually declared themselves as full blown National Socialists during the war as members of organisations like the Ossewabrandwag, the SANP Greyshirts or the Nazi expansionist “New Order”: Oswald Pirow, B.J. Vorster, Hendrik van den Bergh, Johannes von Moltke, P.O. Sauer, F. Erasmus , C.R. Swart, P.W. Botha and Louis Weichardt to name a few, and there is no doubt that their brand of politics was influencing government policy.

This was the very philosophy the retuning South African servicemen and women had been fighting against, the “war for freedom” against the anti-Judea/Christian “crooked cross” (swastika) philosophy and its false messiah as Smuts had called Germany’s National Socialism doctrine and Adolph Hitler.

Some of these men had been detained during the second World war as “terrorists” (mainly for acts of sabotage against the South African Union in support of Nazi Germany – Hendrik van den Bergh, Johannes von Moltke, Louis Weichardt and B.J. Vorster to name a couple), and now they where in office running the country as members of the National Party and governing elite.

In the 1951 in reaction to this paradiym shift in South African politics to the very men and political philosophy the servicemen went to war against, Sailor Malan formed a protest group of ex-servicemen called the “ Torch Commando” (The Torch). In effect it became an anti-apartheid mass movement and Sailor Malan took the position of National President.

The Torch’s first activity was to fight the National Party’s plans to remove “Cape coloured” voters from the common roll which where been rolled out by the National Party two years into office in 1950.

The Cape coloured franchise was protected in the Union Act of 1910 by an entrenched clause stating there could be no change without a two-thirds majority of both houses of Parliament sitting together. The Nationalist government, with unparalleled cynicism, passed the High Court of Parliament Act, effectively removing the autonomy of the judiciary, packing the Senate with National Party sympathisers and thus disenfranchising the coloureds. This was the first move by the National Party to secure a “whites only” voting franchise for South Africa (reinforcing and in fact embedding them in power).

The plight of the Cape Coloured voters was especially close to most White ex-servicemen as during WW1 and WW2, the Cape Coloureds had fought alongside their White counterparts as fully armed combatants. In effect forging that strong bond of brothers in arms (which so often transcends racial barriers).

The Torch Commando strategy was to bring the considerable mass of “moderate’ South African war veterans from apolitical organisations such as the Memorable Order of Tin Hats (MOTH) and South African Legion (BESL) into allegiance with more “leftist” veterans from an organisation called the Springbok Legion – of which Joe Slovo, who himself was also a South African Army World War 2 veteran and was a key leader, his organization – The Springbok Legion, led by a group of white war veterans who embraced Communism was already very actively campaigning against Apartheid legislation and highly politically motivated.

The commando’s main activities were torchlight marches, from which they took their name. The largest march attracted 75 000 protesters. This ground swell of mass support attracted the United Party to form a loose allegiance with The Torch Commando in the hope of attracting voters to its campaign to oust the National Party in the 1953 General Election (The United Party was now run by J.G.N. Strauss after Jan Smut’s death and was seeking to take back the narrow margins that brought the National Party into power in 1948).

In a speech at a massive Torch Commando rally outside City Hall in Johannesburg, “Sailor” Malan made reference to the ideals for which the Second World War was fought:

“The strength of this gathering is evidence that the men and women who fought in the war for freedom still cherish what they fought for. We are determined not to be denied the fruits of that victory.”

The Torch Commando fought the anti apartheid legislation battle for more than five years. At its height The Torch had 250 000 members, making it one of the largest protest movements in South African history at that time.

DF Malan’s government was so alarmed by the number of judges, public servants and military officers joining The Torch that those within the public service or military were prohibited from enlisting, lest they loose their jobs – this pressure quickly led to the erosion of the organisation’s “moderate” members, many of whom still had association to the armed forces, with reputations and livelihoods to keep.

The “leftist” members of The Torch where eroded by anti-communist legislation implemented by the National Party, which effectively ended the Springbok Legion forcing its members underground (many of it’s firebrand communist leaders, including Joe Slovo, went on to join the ANC’s MK armed wing and lend it their military expertise instead).

In essence, the newly governing National Party at that time could not afford to have the white voter base split over its narrow hold on power and the idea that the country’s armed forces community was standing in direct opposition to their policies of Apartheid posed a real and significant threat – bearing in mind one in four white males in South Africa (English and Afrikaans) had volunteered to go to war and support Smuts – this made up a very significant portion of the voting public, notwithstanding the fact that there all now very battle hardened with extensive military training, should they decide to overthrow the government by force of arms.

There has also been some speculation that the Torch Commando untimely failed because it could distinguish the difference of being a mass Anti Apartheid protest movement or a political arm of the United Party. One political cartoon of the time lampoons The Torch Commando as a hindrance to the United Party.

Sailor Malan’s political career was effectively ended and the “Torch” effectively suppressed by the National Party, so he returned to his hometown of Kimberly and joined his local MOTH “Shellhole” (Memorable Order of Tin Hats – one of the apolitical veteran associations from which the Torch had drawn its supporters).

Sadly, Sailor Malan succumbed on 17th September 1963 aged 53 to Parkinson’s Disease about which little was known at the time. Some research now supports the notion that Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) can bring on an early onset of Parkinson’s Disease, and it is now thought that Sailor Malan’s high exposure to combat stress may have played a part in his death at such a relatively young age. Although he fought in the blue sky over England in the most epic aerial battle to change the course of history, one of the “few” to which Churchill recorded that the free world owes a massive debt of gratitude to, he lies today under an African sun in Kimberley – a true hero and son of South Africa.

It is to the embarrassment now as to his treatment as a South African WW2 military hero that all enlisted South African military personnel who attended his funeral where instructed not to wear their uniforms by the newly formatted SADF. The government did not want a Afrikaaner, as Malan was, idealised as a military hero in death in the fear that he would become a role model to future Afrikaaner youth.

The “official” obituary issued for Sailor Malan published in all national newspapers made no mention of his role as National President of The Torch Commando or referenced his political career. The idea was that The Torch Commando would die with Sailor Malan.

All requests to give him a full military funeral where turned down and even the South African Air Force were instructed not to give him any tribute. Ironically this action now stands as testimony to just how fearful the government had become of him as a political fighter.

A lot can be said of Sailor Malan as a brilliant fighter pilot, even more can be said of political affiliation to what was right and what was wrong. He had no problem taking on the German Luftwaffe in the greatest air battle in history, and he certainly had no problem taking on the entire Nationalist regime of Apartheid South Africa – he was a man who, more than any other, could quote the motto of the Royal Air Force’s 74 Squadron which he eventually commanded, and say in all truth:

“I fear no man”

The campaign to purge the national consciousness of The Torch Commando, The Springbok Legion and Sailor Malan was highly effective as by the 1970’s and 1980’s the emergent generation of White South Africans had never heard of them (especially in the Afrikaans community), and even more so to the Black political consciousness who knew even less about these early “white” mass protests against Apartheid.

This “scrubbing” of history by the National Party in aid of their political narrative strangely also aids the ANC’s current political narrative that it is the organisation which started mass protests against Apartheid with the onset of the “Defiance Campaign” on the 6th of April 1952 led primarily by Black South Africans. Whereas the truth of that matter is that the first formalised mass protests in their tens of thousands against Apartheid where in fact led by White South Africans and more to the point mainly white military veterans starting a year earlier in 1951. Another inconvenient truth – luckily history has a way of re-emerging with facts.

Authors note: the purpose of his article is not to have a bash at the politics of the National Party or the ANC, the purpose is also not to drag apolitical organisations like the MOTH or the SA Legion into political debate – the purpose is to set the historical record strait and highlight the veterans role in it, far too much is wrong in the way South African statute force military veterans (then and now) are treated or perceived – the facts and “truth” can yet yield some surprises.

Written by Peter Dickens

References: South African History On-Line (SAHO), South African History Association, Wikipedia ,Neil Roos: Ordinary Springboks: White Servicemen and Social Justice in South Africa, 1939-1961.